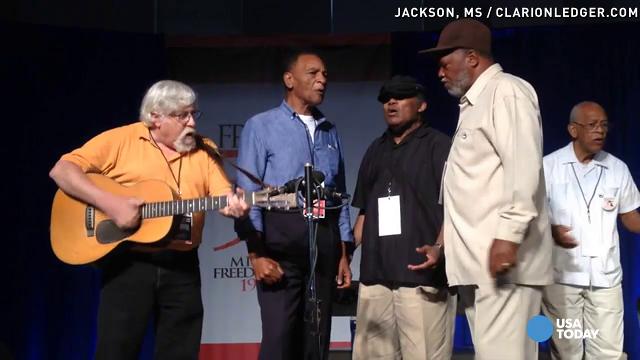

How the Freedom Singers fueled the civil rights movement through music and song

At first, Charles Neblett rejected the call to join a singing group. He had been working in the Mississippi Delta in 1961 helping with the daunting task of registering Black residents to vote.

But Neblett listened as Bob Moses, a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi, explained the mission.

“He sat and told me that what you'd be doing – singing and taking a message throughout the North and the South – will be just as important as you working down here,’’ Neblett, now 80, recalled.

Neblett headed to southwest Georgia where he joined three other activists and formed the Freedom Singers, a group credited with raising money for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), recruiting other activists and performing inspiration songs still sung around the world.

“To tell the story of the civil rights movement through song that was the purpose of the group,’’ said Rutha Mae Harris, 81, one of the original members. “It worked.’’

The Freedom Singers traveled the country in the early 1960s logging more than 50,000 miles and performing in 46 states in nine months. They sang in churches, YMCAs and concert halls. They took the stage at the 1963 March on Washington where they sang "We shall not be moved'' and more recently at the White House in 2010 where they performed, ''Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around."

Black communities have long turned to music for inspiration and comfort, experts said. The Freedom Singers were essential to bolstering the civil rights movement.

“It is freedom songs that gave momentum to the movement and also allayed people's fears,’’ said Daphne Chamberlain, associate professor of history at Tougaloo College in Mississippi. “Just like the call and response songs sung during slavery, freedom songs were messages that gave hope to people and messages that also outlined what a better future looked like for Black folks.”

Freedom songs were inspired by gospel, Negro spirituals, R&B and blues, said Harris. The group would sometimes change lyrics of songs to fit the moment or demonstration.

Neblett said his favorite song was, "Oh Freedom."

"It told what our commitment was,'' he said. "Before you bow down in this mess you'd die. I believed in that."

The lyrics read:

Harris said singing such powerful songs helped ward off fear.

“Without the songs, I personally believe there wouldn't have been a movement because the songs kept people from being afraid,’’ she said. “They took away some of the noise, the clanging of nightsticks, the shots and the dogs, the cattle prods. They took away all that kind of stuff. The songs kept us alive.”

'We sang so much that we lost our voices'

Neblett, Harris, Bernice Johnson Reagon and the late Cordell Reagon, who recruited the singers, were among the original Freedom Singers. Bettie Mae Fikes later joined.

Before joining the group, Neblett, who had been a student at Southern Illinois University, had been singing with Cordell Reagon in other places in the South.

“Singing in jail, singing in the mass meetings and singing on the street,’’ Neblett said. “It displaced fear. When you see them coming, the Ku Klux Klan ... (activists) started singing. The people would regroup and settle down and sing.’’

Harris, a native of Albany, Georgia, and then a student at Florida A&M University, had been singing at mass meetings there when she was asked to join the group. Harris had come home the summer of 1961 to work on voter registration.

“I wanted to fight for my freedom and that's what was going on in Albany, Georgia,’’ Harris said. “I didn't want anybody to say, 'I got your freedom for you.' I wanted to say I got my own freedom, the little freedom that I have.''

The singers recruited others, including many in the North, to join the movement.

“We never looked at ourselves as entertainers,’’ said Neblett. “We looked at ourselves as organizers, so we organized through music.”

Singer Pete Seeger had suggested SNCC form a singing group to tour the country and raise money.

The thought was that the group could do for SNCC what the Jubilee Singers did for Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. The ensemble, which was organized in 1871, toured the country and Europe singing Negro spirituals and other songs and raising money for the historically Black university.

At one point, said Neblett, the Freedom Singers were sometimes performing three concerts a day. “We sang so much that we lost our voices,'' he said.

The fight against racism in America: Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

'We were praying and singing'

While on tour, the group stayed in local homes, often those of white people. The group flew to the March on Washington on singer Harry Belafonte’s private plane.

But there were some harrowing times.

Harris said her scariest moment was when the Buick they were riding in was shot at as they were leaving Alabama after a concert. No one was hurt.

“We were praying and singing,” she said. “(We sang) Come by here, my Lord.”

Civil rights veterans said freedom songs kept them going when they were jailed or marching.

Thomas Gaither, 83, and other members of the so-called Friendship Nine – a group of nine Black college students – sang the songs when they chose to do 30 days in jail in protest instead of paying bail after staging a sit-in at a lunch counter in 1961 in Rock Hill, South Carolina.

“We would break into courses of freedom songs,’’ said Gaither, adding that it often irritated prison officials. “They would say, ‘Shut up! Stop that damn fuss or something of that sort.’ But we continued to sing freedom songs and we could actually engage some of the prisoners who knew the songs.”

Some Freedom Singers still perform.

The Albany Civil Rights Institute Freedom Singers, formed by Harris, perform every second Saturday for visitors to the institute. The institute also has a group of younger Freedom Singers, who must first learn what the lyrics mean before they can perform.

“We’re keeping the songs alive,’’ Harris said. “The songs of the civil rights movement are still important.”

Contributing: Wenei Philimon

Follow Deborah Berry on Twitter: @dberrygannett

How we can heal from racism: Black national anthem would become America's hymn under proposal