Rarely used in modern times, quarantine laws give public officials wide-ranging powers

Inside a shining new medical quarantine unit in Omaha, Nebraska, eight evacuees from the Diamond Princess cruise ship remain under armed guard as they recover from coronavirus infections.

Though the doors to their rooms aren't locked, U.S. marshals enforce a rarely used federal quarantine order preventing the men and women from going home until they've recovered. Opened last year, the 20-bed National Quarantine Center is the nation's only specifically designed federal site where people suspected of having high-risk infections can be securely detained.

"The whole tenet of public health is temporarily giving up some personal liberties for the greater good," said Dr. Angela Hewlett, an infectious-disease expert and leader of the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, which is associated with the quarantine center. "We haven't had anyone who has tried to escape."

As cases of disease from the new coronavirus spread across the country – topping 1,300, including 39 deaths, as of Thursday afternoon – more Americans find their daily lives altered by public officials, and quarantine orders and "social distancing" requests are growing.

Tuesday, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered the National Guard to help manage quarantine for a section of the town of New Rochelle after doctors discovered a series of infections. The next day, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee banned all gatherings of more than 250 people in three counties, including the Seattle area. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis followed suit Friday, ordering all mass crowd events postponed or canceled for the next 30 days. Hours later, Cuomo did the same.

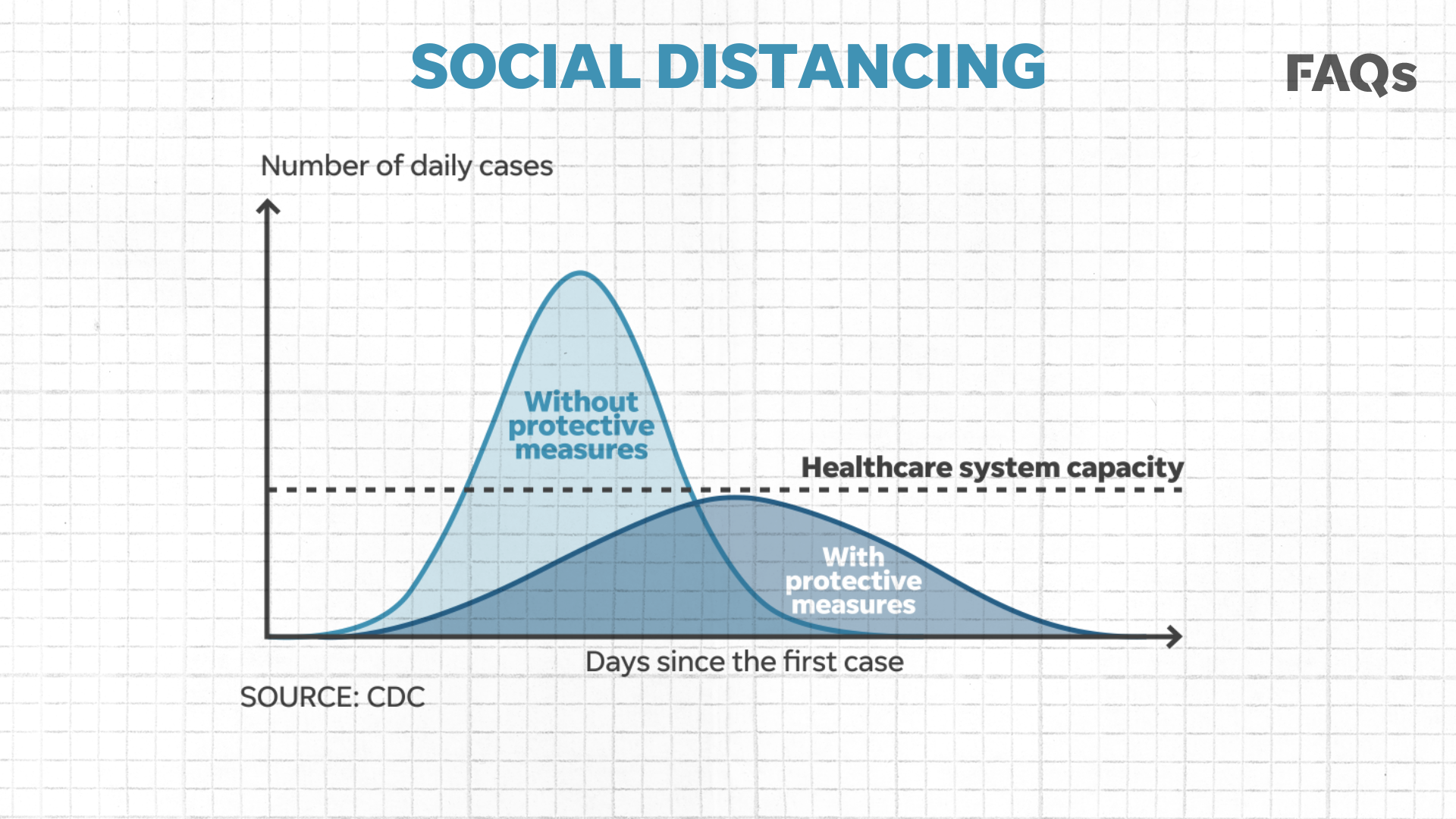

Experts said quarantines are effective in controlling the outbreak because the coronavirus spreads easily through droplets from coughs or sneezes. Scientists are studying how long the virus can survive, but some research shows it can stay in the air for hours and on surfaces for two or three days.

The recent actions highlight little-known and rarely used powers of government to narrowly limit the movements and interactions of residents at the expense of individual liberties. Those powers are in addition to the flexibility granted to governors who declared states of emergency to free up funding and expedite response.

State and federal authorities are dusting off long-shelved plans to force Americans to stay in their homes; ban public gatherings, including sporting events; close schools; and restrict travel in ways that seemingly violate constitutional protections.

The last time the U.S. government mandated large-scale quarantines was more than 100 years ago during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19 (a much smaller effort surrounded the Ebola outbreak in 2014). Scientists and public health officials are battling both the new coronavirus and the skepticism of a society that hasn't seen a similar epidemic or quarantines for generations, said Glen Mays, professor and department chair in the Colorado School of Public Health at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus.

"That's part of the challenge. Infectious diseases are not the killers of our population that they were 50 years ago," said Mays, who studies health system emergency preparedness. "We've got more skepticism around these issues. You see that in vaccinations and vaccinations rates. Part of that may represent some complacency. We fought back these infectious diseases decades ago."

Studies show that governments willing to use those powers saved millions of lives during the Spanish flu pandemic, while those that didn't saw greater casualties.

At the epicenter of the current pandemic, the communist government in China swiftly moved to contain the new coronavirus by mandatory restrictions on the movements of millions of people. Such decisions are trickier in a democracy that prides itself on self-determination. Politicians and experts must make their case to a public that may be skeptical of both the risk and, in some cases, the basic science of medicine.

Experts said U.S. residents should expect widespread efforts to curtail their movements as the viral infection grows. Those efforts will include isolation – the lockdown of an individual person who is known to be sick – and quarantines, which are broader restrictions on people who have been exposed but aren't actually ill.

Although public health officials have the legal authority in every state to order quarantines and "social distancing," efforts are most effective when people voluntarily abide by them, said Eric Cioe-Pena, director of global health for Northwell Health, New York's largest health care provider. Many large employers have asked their employees to work from home.

Cioe-Pena, a medical doctor who holds a master's degree in public health, has isolated patients with contagious diseases, such as tuberculosis. Most people, he said, abide by orders once they understand that although they might not be that sick, they're putting their loved ones at risk.

"What we've found is that voluntary quarantines are actually pretty effective," he said. "People, in general, when faced with this on an individual level, are understanding about the situation."

Though specific quarantine and isolation powers vary across the country, many are similar to those in Colorado, where public health officials can order a quarantine and require people to report their temperature and other symptoms daily, along with potential in-home visits by doctors. State officials prefer to work collaboratively with quarantined people, but a judge could order them detained, and if they refuse to cooperate, fine them up to $1,000 and up to a year in jail once they recover.

Mays said his research has shown political leaders must clearly communicate the risks to the public to build and maintain support for travel restrictions and quarantines.

"It is a big challenge and one that the public health system confronts routinely," he said.

In suburban Seattle, public health officials bought an EconoLodge hotel to use as a coronavirus quarantine facility, alarming area residents and business owners who want assurance sick people won't be transported there, then allowed to wander the community. How will those quarantined be kept on the site?

"I mean, are they going to have guards with machine guns walking around?" asked Robert Tegtmeyer, 51, co-owner of the Kent Bowl bowling alley across the street. "I don't want sick people coming over here."

Craig Fugate, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency under President Barack Obama, said political considerations always play a role in ordering widespread quarantines.

"It becomes a cost vs. benefit political decision," he said. "How many could die if you don’t? How much of the public will rebel if they don’t buy into the danger of not quarantining folks. Freedom of movement and individualism tend to work against public good. Selfish people don’t care unless they feel threatened."

In Omaha, where she monitors the quarantined Diamond Princess patients, Hewlett said simple isolation works really well, despite how low-tech it might seem in an age of MRI scanners, robotic surgery and instant-read thermometers.

"Remember Typhoid Mary? They stuck her on an island off New York City," Hewlett said. "Even with all of our technology, keeping people away from each other is still an effective way of preventing the spread of disease."