Minnesota judges hide jurors' names when police go on trial in killings

Anonymous juries are supposed to be a rarity in U.S. courts, a way to protect jurors from influence, retaliation and even harm, typically in cases involving gangs and terrorists.

In Minnesota, judges hide jurors' names from the public when the cases involve a police officer who faces criminal charges for killing someone while on duty.

Since 2016, four law enforcement officers have been put on trial in Minnesota for killing someone on duty. All but one of those cases have been decided by an anonymous jury.

In April, an anonymous jury convicted former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin of murder and manslaughter for George Floyd's death. Four months later, their identities are still being withheld by the judge.

"Anonymous juries are supposed to be very rare, and historically, they have been very rare," said Minneapolis attorney Leita Walker, who represents a coalition of news outlets seeking to unseal the names of the Chauvin jurors.

"What we’re seeing in very recent history in Minnesota is trial courts developing an exception for cases that involve police officers," she said in an interview. "And that exception is not recognized in the law."

Chauvin verdict analysis: Anonymous jury in Derek Chauvin trial part of a growing trend that has some legal experts worried

Jury makeup: Here are the jurors who will decide whether Derek Chauvin is guilty of murder in George Floyd's death

The latest Minnesota officer expected to face an anonymous jury is former Brooklyn Center officer Kimberly Potter. She is scheduled to stand trial this fall on a charge of second-degree manslaughter in the killing of Daunte Wright, 20, during a traffic stop.

Juror names are supposed to be public in the U.S. An open and transparent judicial system is meant to build confidence that the process is fair and jurors are not corrupt or tainted.

The one trial of a law enforcement officer in which jurors' names weren't hidden involved two white men. Washington County Sheriff's Deputy Brian Krook was acquitted of manslaughter in the fatal shooting in 2018 of firefighter Benjamin Evans, 23, who was suicidal.

In all the cases in which jurors' names have been hidden, the victim or the officer was Black. Mohamed Noor, the first police officer to be convicted of murder in modern Minnesota history, is Black. He was convicted of killing a white woman.

"I don’t think that it's difficult to draw a straight racial argument," said prominent civil rights lawyer John Burris, who represented Rodney King. "Racial judgments are being made here as to the publication of jurors' (names) and the anonymization of them. It should not be."

Rodney King trial, 30 years later: Trials of police who beat King compared to Chauvin, who kneeled on George Floyd's neck

Kim Potter case: Prosecutor assigned to case of ex-cop charged in Daunte Wright's death resigns over 'vitriol' and 'partisan politics'

News outlets want judge to release jurors' names in Chauvin trial

Floyd's death was captured on bystander video and spurred weeks of protests, some of which turned violent. That led defense attorneys and Hennepin County District Court Judge Peter Cahill to worry they wouldn't be able to find an impartial jury.

Cahill decided to withhold jurors' names, so they wouldn't be subject to public pressure or harassment. Because the courtroom couldn't accommodate four defendants during the pandemic, he split Chauvin's trial from the three other officers involved in Floyd's death. Chauvin's trial was livestreamed because the courtroom was closed to observers.

Jury selection process: 12 jurors must set aside what they saw in the George Floyd video. How will lawyers find an impartial jury?

During jury selection, some potential jurors expressed comfort in knowing their names would be hidden from the public for some period, said Mary Moriarty, the former chief public defender for Hennepin County.

After jurors convicted Chauvin in April, Cahill decided their names would remain hidden until at least October.

The media coalition, which includes Paste BN, filed a motion to unseal jurors' names and other materials, including questionnaires they filled out during the selection process.

The coalition said in a court filing that "the public interest in this case and the national reckoning to which it gave rise make transparency regarding the identities, backgrounds, and predilections of the people who handed down the verdict more important, not less."

The Minnesota Attorney General's Office opposes releasing the names. It argued in a court filing that identifying jurors would "hamper efforts to assure prospective jurors in the March 2022 trial involving Mr. Chauvin's three co-defendants that their identities will be protected."

In a possible preview of arguments, they said the court shouldn't revisit its order "mere months" before that trial and potential federal proceedings.

It's unclear whether jurors in the other officers' trial will be anonymous.

The Attorney General's Office said in its court filing it doesn't know of any harassment faced by jurors, but it said that could be because their identities remain under seal. Two jurors and an alternate in Chauvin's trial went public and have not publicly commented on any harassment.

Prosecutors reverse position on unnamed jurors

Last September, the Minnesota Attorney General's Office took the opposite position, strongly objecting to an anonymous jury, according to a filing Friday by the media coalition.

In a court hearing in September 2020, prosecutor Matthew Frank argued that the case didn't meet the standard for shielding jurors' names, which he said is an "extreme measure" that isn't taken even in some cases involving retaliatory gang murders.

Frank said shielding jurors' names is akin to closing a courtroom, where "we're conducting business to an extent secretly."

Cahill said that his primary concern was not jurors' safety but their impartiality and that the names would be released "shortly" after the trial as long as there was no civil unrest, the media coalition said in its filing.

Officials were on guard for violence after the verdict. Barricades and razor wire were set up near the courthouse, and thousands of National Guard troops were called in.

But the guilty verdict was met with "community relief rather than unrest," the coalition's filing said. "And yet the jurors' names remain secret."

One of Chauvin's co-defendants wants jury to be identified

Former officers Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao face charges of aiding and abetting Chauvin in committing murder and manslaughter.

Kueng's attorney, Thomas Plunkett, told the court last fall he opposes an anonymous jury because it violates his client's constitutional right to a fair and open trial.

"It reflects the general rule that judges, lawyers, witnesses and jurors will perform their respective functions more responsibly in an open court than in a secret proceeding," Plunkett told the court.

Plunkett told Cahill that shielding jurors' names "sends a message" that the jury is in danger. He declined to comment to Paste BN.

Trial delayed: 3 former police officers accused in George Floyd's death won't stand trial until March 2022

A study in 1998 examined the impact of juror anonymity in university disciplinary hearings. It found that anonymous juries convicted at a higher rate than named juries – 70% compared with 40% – when evidence against the defendant was strong.

Defense attorneys say jurors typically give police officers the benefit of the doubt when they're charged with a crime.

Anonymous juries, according to the study, imposed the harshest punishment available more often than identified juries. The study did not find that anonymous jurors felt less accountable than named ones.

Judge in Kim Potter case shields jurors' names

Wright's death, which occurred during Chauvin's trial, also led to protests, but they calmed down after several days.

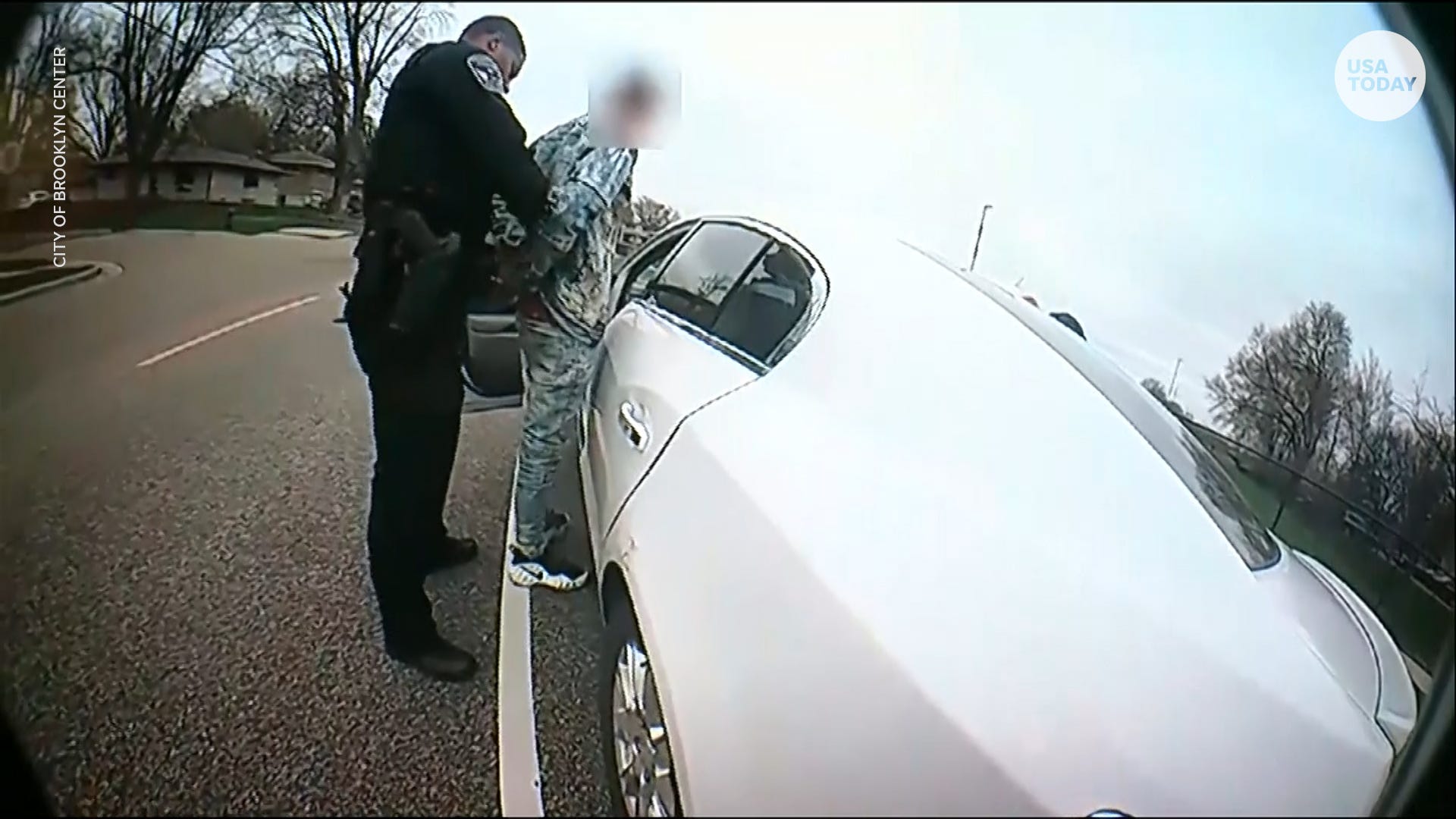

Brooklyn Center's then-police chief said Potter, a 26-year veteran of the department, accidentally fired her handgun rather than her Taser. The department released body camera footage that shows Wright struggling with police and Potter shouting, "Taser!" three times before firing.

Hennepin County District Court Judge Regina Chu issued an order last month shielding jurors' names in the Potter case. The order said their names will be hidden until Chu decides otherwise.

"The judges in both cases are balancing the safety of the jurors against the public’s right to know," said Joseph Daly, emeritus professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law.

To properly strike a balance, judges need to assess whether there are facts – not just speculation – indicating jurors are in danger, Daly said. Judges must carefully analyze their own possible implicit biases.

Under state law, a judge must have a strong reason to believe there are external threats to juror safety or impartiality to restrict access to their names and other identifying information.

According to the Minnesota Supreme Court, a trial judge must include in the record "a clear and detailed explanation" of the facts that show a jury needs protection.

Chu didn't explain her reasoning in her three-page order; she simply cited state law.

It's unclear how the issue came up in the Potter case. Chu's order was issued after an off-the-record scheduling conference, so no transcript exists, court spokesman Spenser Bickett said in an email. Paste BN reached out to Chu and lawyers for both sides; none responded.

Minnesota Attorney General's Office spokesman Keaon Dousti said in an email that "as far as I know, this was Judge Chu's decision on her own."

Potter in court: Ex-Brooklyn Center police officer Kim Potter appears in court as Daunte Wright's family demands accountability

Though Potter's fatal shooting of Wright occurred within miles of where Floyd was murdered, Moriarty said it's a completely different case. Wright's death didn't last 9½ minutes, and video didn't spread around the world.

"Transparency is very important, and it should be rare that a judge takes the extreme step of making the jury anonymous," Moriarty said. "That shouldn’t be automatic in a case where a police officer is on trial."

Why are jurors' names public?

The use of anonymous juries has grown over the past several decades as technology has made it easier to track people down and harass them.

Jurors' names have been hidden for high-profile cases involving O.J. Simpson, Mafia boss John Gotti, R&B star R. Kelly and two of the Los Angeles police officers accused of assaulting Rodney King.

Minnesota's first anonymous jury, in 1995, convicted an alleged street gang member for an assassination-style slaying of a Minneapolis police officer.

One reason their names were hidden was that a witness had been killed, allegedly because gang members thought he was talking to the police about the killing, according to a state Supreme Court opinion.

In his order sealing jurors' names for the police involved in Floyd's death, Cahill cited harassment and threats against the defendants and their lawyers, including incidents outside the courthouse and a defendant's home.

When jurors remain anonymous, "no one can question them or their decisions," a William Mitchell Law Review article noted in 1996. "Scrutiny by the public of a jury's decision will likely have no impact on the fate of the defendant. A jury which knows that others will examine its decision, however, might feel more societal pressure to render a fair verdict."

A.L. Brown, a St. Paul, Minnesota, attorney, said he "could make a very strong argument that (the names) should absolutely be made public. Maybe someone says, 'John on the jury, he drops the n-word every other day.'

“The other side of the argument,” he said, “is, ‘Oh my gosh, Sally on the jury lives next door, and I'm going to torment her for the next month on this trial until she convicts this guy.’”

Brown said it would be unfair for all officers charged with crimes to face unnamed juries by default, especially given their positions of power compared with other defendants. A high-profile case isn't enough of a reason to justify anonymity, he said.

In the cases of Chauvin, his co-defendants and Potter, the jury had not been selected when the judge decided their names would be hidden. "At least get a jury in the room and ask them if it’s a concern," Brown said.

If security is such a concern, he said, the judge should sequester the jury, even if it is inconvenient.

"You can inconvenience the 12," Brown said, "or you can inconvenience the 5 million Minnesotans."

Tami Abdollah is a Paste BN national correspondent covering inequities in the criminal justice system. Send tips via direct message @latams or by email tami(at)usatoday.com