Pearl Harbor, 80 years on: Veteran Doris Miller's legacy can be felt at home and across the country

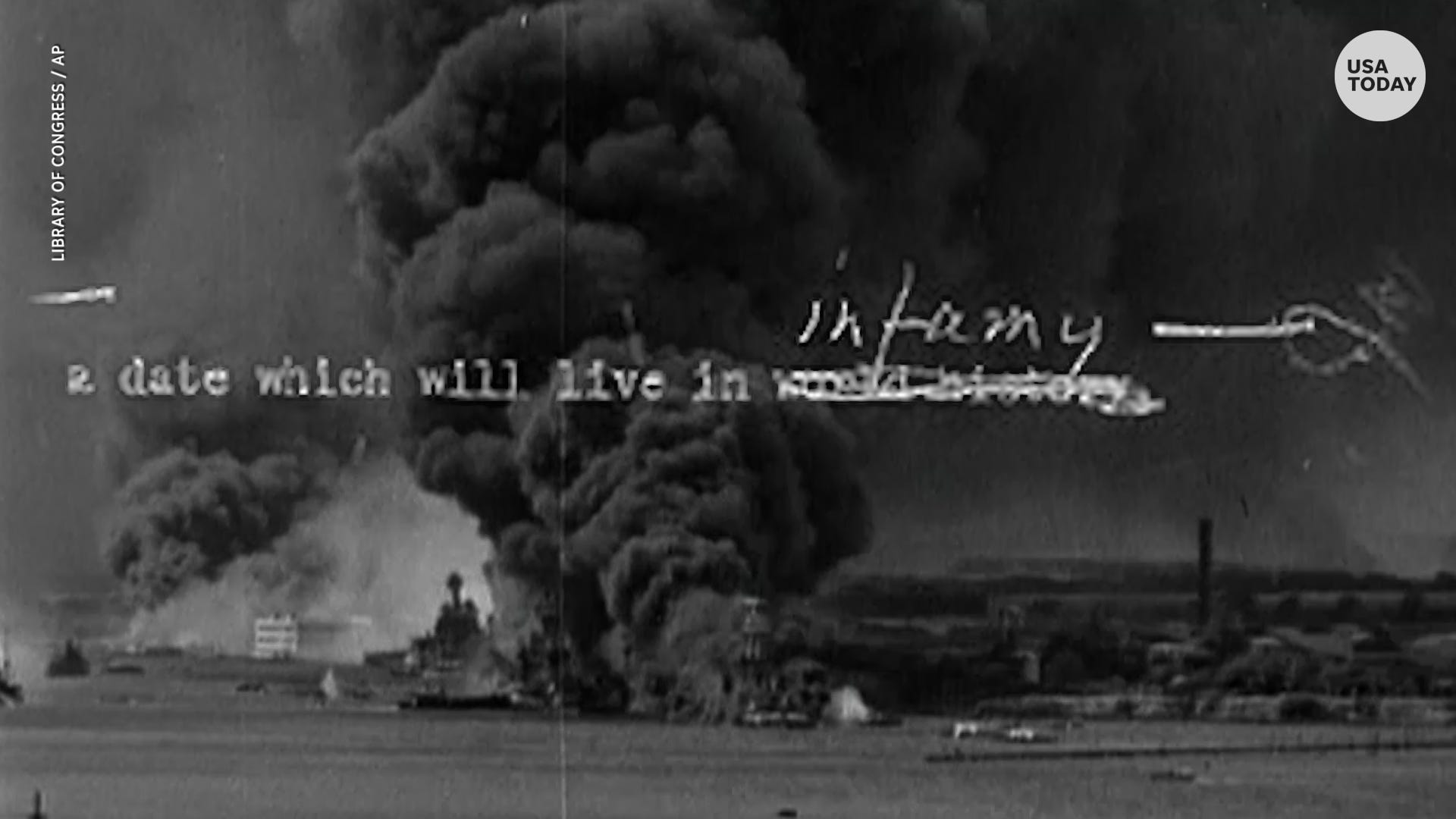

BREMERTON, Wash. — Doris Miller awoke before dawn and was gathering laundry aboard the USS West Virginia on a December morning 80 years ago when alarms rang out.

As Japanese aircraft pummeled Pearl Harbor, the 22-year-old mess attendant from Waco, Texas, placed himself in the line of fire on the battleship's deck, carrying wounded men to safety and eventually grabbing and firing a Browning machine gun he was untrained to use because of the color of his skin.

Despite his bravery, Miller never wanted to be a war hero.

"All he wanted to do was get to his next ship," said Regina T. Akers, a historian with the Navy's history and heritage command. "He wasn't really that comfortable with the spotlight."

America had other plans for him.

Pearl Harbor 'led to a changed world.': 80 years later, a fading memory will be honored again.

Posters of Miller went up in storefronts as a nation once divided at the prospect of another world war coalesced behind President Franklin D. Roosevelt's vow that the country would "achieve absolute victory." Miller was paraded to war bonds drives and visited recruiting centers to help inspire others to join the war effort.

But the soft-spoken Miller also helped to galvanize a movement in a segregated America. In the Navy, Black men could only work in the kitchen or do laundry. For three months after Pearl Harbor, his heroics were described only as a "Negro mess attendant" while others were immortalized with the Medal of Honor.

Civil rights groups and leaders, Black newspapers and members of Congress began to press for change in Miller's name. They began to call for a "Double V," or a victory for democracy overseas and at home.

In the 80 years since Pearl Harbor, Miller's story has been venerated countless times. His actions were memorialized in the classic 1970 film "Tora! Tora! Tora!" as well as in the Michael Bay blockbuster "Pearl Harbor" in 2001. And in 2020, the Navy announced an honor typically reserved for U.S. presidents: His name will grace the fleet's newest aircraft carrier.

Relics of the USS West Virginia speak to Miller's bravery as one of World War II's most recognizable heroes — but also to the message that reverberated around the country: "a reaffirmation that Blacks and whites can serve together," Akers said.

"He is a reminder that diversity is a strength for the Navy," she said.

Akers said Miller is all the more inspiring given that, though he faced racism and segregation in his own nation, he put himself in harm's way without hesitation.

"Despite living in a segregated country, one with discrimination by custom, law and tradition, he still wanted to serve," Akers said.

'I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine'

Miller was born in October 1919. One of four brothers, he played fullback on his high school football team and worked on his father's farm before he enlisted in the Navy.

Miller walked into a recruiting station on Sept. 19, 1939. There were only 4,000 African American men in the Navy at the time and all served duties limited to either doing laundry or cooking, according to a report by Neil Sapper in the East Texas Historical Association.

Third-class mess attendant Miller rose as he could through the ranks, being promoted to a third-class cook and becoming the USS West Virginia's heavyweight boxing champion after being transferred to the battleship in January 1940.

As Japanese planes strafed the decks of the battleship on Dec. 7, 1941, Miller attempted to get to his battle station, but a torpedo had destroyed the antiaircraft battery.

The West Virginia, like others in the harbor, was bombarded. A Japanese force of six aircraft carriers sent more than 350 aircraft over two waves to the unknowing Pacific Fleet. Japanese planes launched five aircraft torpedoes into the West Virginia's port side to go with two armored piercing bombs, which penetrated its deck.

The deck, in the face of grave danger, is exactly where Miller went.

As he turned his attention to rescuing the wounded, he was ordered to get the battleship's commanding officer, Capt. Mervyn Bennion, to safety. It was too late for him, however, and another officer ordered Miller to get ammunition to some machine guns on deck as fires exploded around the ship.

Miller did more than supply ammo. Despite his lack of experience — Black people weren't given gunnery training — Miller took hold of a 50-caliber Browning anti-aircraft machine gun and pulled the trigger.

"It wasn't hard," Miller was quoted as saying after the attack. "I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine."

It's unknown to history how many planes he shot down but it's likely between one and six, according to differing accounts. One thing's sure: Miller kept shooting until he could no longer.

The West Virginia — transformed into an inferno above the decks while flooding waters raged below — began to sink, and its crew was forced to abandon ship. The losses on board numbered 130, to go with more than 2,400 who died that day. The West Virginia was one of five battleships sunk, along with a number of other ships.

News of Miller's heroism emerged much more slowly than that of white sailors. In all, 15 sailors — including 10 who succumbed to mortal injury — were awarded the Medal of Honor. But not Miller. He was simply known as a "Negro mess attendant" until pressure from the NAACP, members of the Black press and those in Congress pushed the Navy to acknowledge his heroism. Finally, on May 27, 1942, Miller received the Navy Cross from Adm. Chester Nimitz, the commander of the Pacific Fleet and a fellow Texan.

Nimitz pointed out at the ceremony that it was the first time "a member of his race" had received the Navy Cross, and the admiral was sure "that the future will see others similarly honored."

Nimitz recognized that Miller's example would help recruit African Americans to the cause, Akers said. But it would take years for Black men and women to be fully integrated into the branches of the military. Though President Harry Truman ordered discrimination based on "race, color, religion or national origin" abolished in the military in 1948, it was several more decades before the Navy took integration seriously, the Navy's history and heritage command says.

Miller, typically a man of few words, wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper, on its advocacy for the betterment of African Americans: “You have opened up a little for us, at least for the ones who were following me, and I hope it will be better in the future.”

Though the West Virginia was sunk at Pearl Harbor, the Navy was not willing to let go of it. Along with 12 other ships sunk at Pearl Harbor, the battleship was brought back from the grave. Divers patched holes in its hull, its heavy fuel and munitions were removed and it was pumped to get it buoyant again. The salvagers found some 66 sailors' remains, including in the compartment where bulkhead marks indicated three men had hung on for 16 days following the attacks until their air ran out.

The ship, part of what was known as the "ghost fleet," was floated back to Bremerton and ultimately repaired. Around the same time it got to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, so did Doris Miller.

Miller, who had gotten to spend time with family in Waco one last time, arrived at the Puget Sound Navy Yard on May 15, 1943. He was assigned to a brand new carrier, the USS Liscome Bay, a 512-foot-long aircraft carrier built by Kaiser Shipyards in Vancouver, Washington.

The ship came here following commissioning for radio equipment and compass work, according to Megan Churchwell, curator of the Puget Sound Navy Museum. How Miller spent his time in Bremerton and where he lived is unknown, but it's likely he didn't stray far from his new ship.

After steaming south to California, the ship deployed to the Pacific Theater. Participating in the invasion of the Gilbert Islands, the carrier was struck by a torpedo launched by a Japanese submarine on Nov. 24, 1943. It was a devastating strike, killing 644 people, including Miller. Only 272 survived, and it is to this day the deadliest sinking of a carrier in the country's history.

The USS West Virginia's repairs, meanwhile, took years. Only in July 1944, after outfitting the ship with updated fire-control equipment and radar, was the battleship ready to "exact her toll on Japanese forces," according to an essay by the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

The "Wee Vee" was the only battleship sunk at Pearl Harbor to appear in Tokyo Bay for the signing of the Japanese surrender in 1945. In 1947 it was decommissioned, and it was ultimately dismantled 12 years later. It was towed to Todd Pacific Shipyards in 1961, where it was officially scrapped. Many relics from the ship are now scattered across the country, including in Bremerton.

The aircraft carrier being built in Miller's name, meanwhile, won't be laid down until later this decade and likely not in service until the next one. Akers said the Navy's decision to name an aircraft carrier after Miller carries "enormous" implications.

"For generations to come they'll be talking about Doris Miller," she said. "He reminds us that that where one starts is not an indicator of where one can finish."

Josh Farley is a reporter covering the military and Bremerton for the Kitsap Sun. Follow him on Twitter: @joshfarley.