Giant meteorite that hit Earth 3 billion years ago may have helped life thrive: Study

Harvard researchers found that when a meteorite nicknamed S2 paid a visit to our planet 3 billion years ago, instead of ending life, the space rock may have allowed it to thrive and grow.

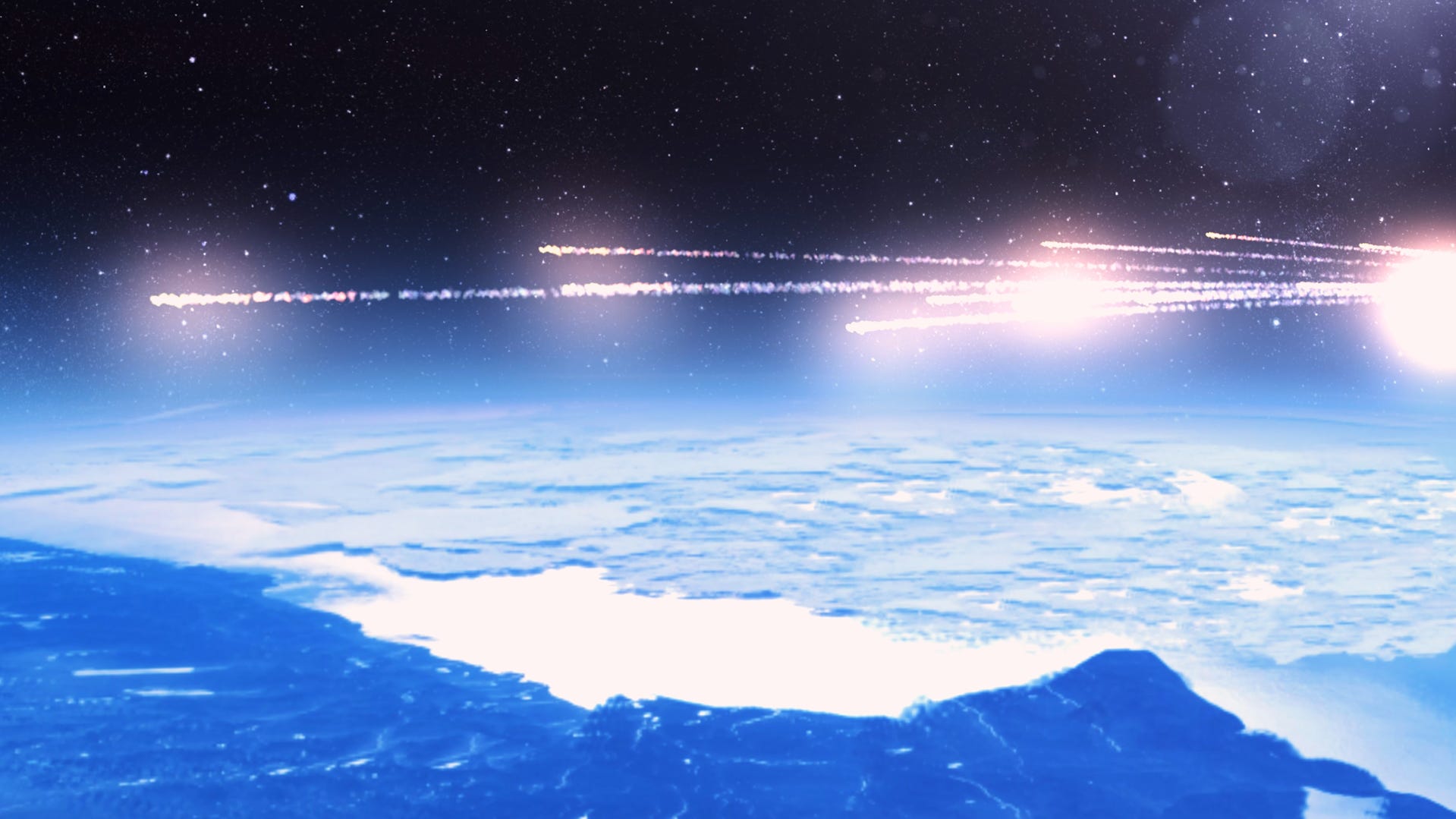

When a gargantuan space rock, estimated to be the size of four Mount Everests, crashed into Earth more than 3 billion years ago, many may assume that it would have wreaked havoc on a young planet.

After all, that's what happened much more recently – just a few short 66 million years ago, to be exact – when a massive asteroid slamming into Earth is believed to have caused catastrophic devastation and wiped out the dinosaurs.

But Harvard researchers found that something much more unlikely happened when a meteorite nicknamed S2 paid a visit to our planet. Instead of ending life, the space rock may have allowed it to thrive and grow.

That doesn't mean its collision with Earth wasn't cataclysmic.

What would it have been like to experience such an impact? Nadja Drabon, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University, explains it like this:

“Picture yourself standing off the coast of Cape Cod, in a shelf of shallow water. It’s a low-energy environment, without strong currents," Drabon said in a statement. "Then all of a sudden, you have a giant tsunami sweeping by and ripping up the sea floor."

Drabon, the lead author of the new study describing the aftermath of S2, recently led a team that visited the impact site in the Barberton Makhonjwa Mountains of South Africa to hunt for geological evidence of the collision.

Here's what to know about the team's findings, published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Evidence of impact found at Barberton Greenstone Belt

The Barberton Makhonjwa Mountains are home to a geologic formation known as the Barberton Greenstone Belt where eight impact events, including the S2 meteoritic impact, have occurred.

That's where Drabon and her students conducted fieldwork – hiking into mountain passes to collect and examine rock samples embedded in the ground and preserved in Earth’s crust.

The sedimentary samples contained chemical signatures hidden in thin layers of rock that helped Drabon and her students paint a picture of the tsunamis and other cataclysmic events S2 wrought.

S2 impact allows bacteria life to flourish

The aftermath of space rocks crashing into Earth usually conjure associations with the gigantic object known as the Chicxulub impactor, which ushered in the end of the dinosaurs when it crashed in modern day Mexico on the Yucatán Peninsula.

But dinosaurs were still a long time away from roaming Earth when S2 crashed down about 3.26 billion years ago. The meteorite was estimated to have been up to 200 times larger than the extinction-inducing Chicxulub asteroid.

That massive size made it plenty large enough to trigger a devastating tsunami that mixed up the ocean and flushed debris from the land into coastal areas. The crash into Earth also heated the atmosphere, boiled off the topmost layer of the ocean and blanketed the planet in a cloud of dust making photosynthetic activity impossible.

But the impact also carried a silver lining.

“We think of impact events as being disastrous for life,” Drabon said in a statement. “But what this study is highlighting is that these impacts would have had benefits to life, especially early on, and these impacts might have actually allowed life to flourish.”

The iron that was likely stirred up deep in the ocean into shallow waters provided a food source that allowed hardy bacteria life to rebound quickly, according to Drabon's findings. As a result, populations of unicellular organisms spiked.

Drabon and her team plan to visit the area again to continuing probing for clues about how the meteorite shaped Earth's history.

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for Paste BN. Reach him at elagatta@gannett.com