How Halloween helped change daylight saving time

After a long night of trick-or-treating and perhaps staying up late to indulge in the spoils or attend a Halloween party, there's a built-in reprieve: The end of daylight saving time means we get an extra hour to sleep this weekend.

It's no coincidence that the time change comes after the holiday. Up until about two decades ago, daylight saving time ended the last Sunday in October rather than the first Sunday in November, as it does now. That would make sunset an hour earlier, meaning less daylight for kids to go door-to-door.

Daylight saving time aims to save energy by shifting the clocks for part of the year to better align daylight with the times of day that people are working or at school. When (and if) the clocks change has been a debate for years, as lawmakers and advocates squabbled over the schedule.

Currently, the goal of many is to eliminate a disruptive twice-yearly clock change, but lawmakers in the early 2000s came up with a different fix: Move the dates that the clock changes by a few weeks.

The plan, which came in a bill passed by Congress in 2005 and enacted in 2007, was primarily a way to save energy (extending daylight saving time in theory meant less time needing lights in the evening). But it saw support from lawmakers who raised concerns about kids' safety on Halloween, and from lobbyists who said the change would be good for sales in their industries.

It not only put the end of daylight saving time after Halloween, but it also made the start of daylight saving time two weeks earlier than it was before.

Somewhat ironically, the U.S. now says only about four months of the year should be standard time — from early November until early March.

A brief history of daylight saving time

Daylight saving time was first introduced in the U.S. in 1918 when the Standard Time Act became law to save on fuel costs, but it was quickly reversed at the national level after World War I ended, only coming up again when World War II began.

From February 1942 until September 1945, the U.S. took on what became known as "War Time," when Congress voted to make daylight saving time year-round during the war in an effort to conserve fuel. When it ended, states were able to establish their own standard time until 1966, when Congress finally passed the Uniform Time Act, standardizing national time and establishing what we now know as daylight saving time.

In the '70s, daylight saving time was again temporarily established long-term during the oil embargo crisis.

How Halloween influenced daylight saving time

After 1966, daylight saving time was implemented from the last Sunday of April to the last Sunday of October. Twenty years later in 1986, it was amended to start on the first Sunday of April instead.

For years, lawmakers tried to stretch daylight saving time even more in an effort to save energy. In 2005, that finally became reality, and daylight saving time as we know it today became the law. Now, it lasts from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November, notably extending past Halloween.

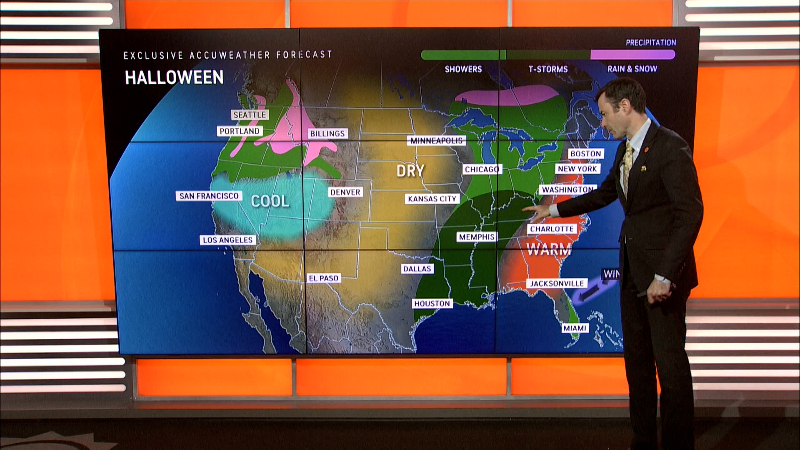

Aside from energy savings, lawmakers at the time said that stretching daylight saving time to include Halloween would make the night safer for children. Halloween is still the deadliest night of the year for child pedestrians, studies show, but advocates said that having an extra hour of daylight to trick-or-treat would make a difference.

On the flip side, some advocates for kids' safety, including the National Parent Teacher Association, opposed the change because they worried that it would mean more morning commute time spent in the dark, a danger to kids walking to school or waiting for a bus.

More than once before the 2005 Energy Bill extended daylight saving time, lawmakers considered a Halloween Safety Act that sought to do the same thing but didn't make it into law.

“Between energy conservation, fewer traffic accidents and keeping kids safe on Halloween, the benefits of extending Daylight Saving Time are many – not to mention the additional hour of sunshine in the evening will help chase away the winter blues,” former Michigan Rep. Fred Upton said in a 2009 news release after the daylight saving time change was in effect.

By some accounts, the candy industry also had a hand in extending daylight saving time.

Michael Downing, author of "Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time," told NPR in 2007 that candy lobbyists "wanted to get trick-or-treat covered by Daylight Saving, figuring that if children have an extra hour of daylight, they'll collect more candy."

Sen. Ed Markey, who was a Massachusetts representative at the time, told the New York Times that energy and safety were the drivers of the change, not the candy industry. And candy industry representatives denied the connection.

Meanwhile, retailers said it would boost business because people would shop more in the evenings before nightfall.

Some now want permanent daylight saving time

Several states have passed measures that would make daylight saving time year-round. The only problem is that federal law prohibits it.

States are allowed to have permanent standard time, which Hawaii, the non-Navajo parts of Arizona and some territories do. In order to have permanent daylight saving time, Congress would need to pass a law allowing it.

A bill that passed the Senate in 2022 but has stalled since then would make year-round daylight saving time the law of the land. The Sunshine Protection Act was introduced by Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida. Rubio and other pro-permanent daylight saving time advocates argue that the benefits include more time for outdoor activities or work in the evening hours, and that it would conserve energy.

Many experts agree that time changes contribute to health issues and even safety problems, but some experts say that year-round standard time would be better.

"It’s time to lock the clock and stop enduring the ridiculous and antiquated practice of switching our clocks back and forth," Rubio said.