Ex-spy chief: 'No secret sauce' stops lone-wolf terrorists

More than spying is needed to stop the kind of carnage suffered last week in Fort Lauderdale and last year in Orlando, according the former head of the CIA and NSA who has who headed intelligence agencies under three presidents.

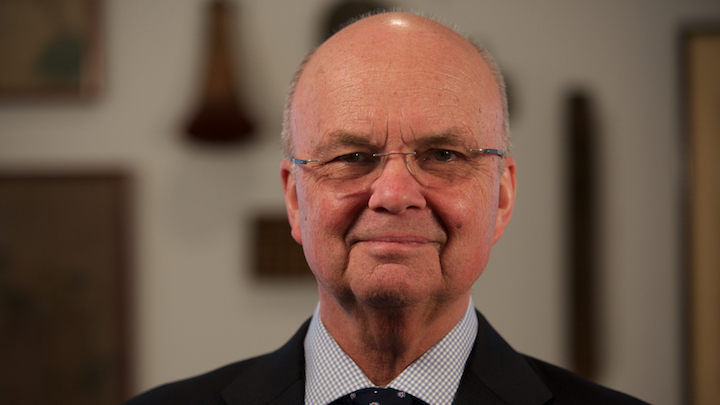

Michael Hayden's advice, which he said is not popular in the world of espionage: Begin a serious conversation without “knee-jerk, rejectionist reactions” about the Second Amendment.

“There is not much more you can do in terms or surveillance that really cranks up the probability I’m going to find the Orlando guy or the Boston Marathon kids or the Chattanooga guy,” said Hayden, who served under presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. “There’s some stuff on the margins that might make it more likely, but there’s no secret sauce.”

The idea is to make would-be lone-wolf attackers, no matter what their political views, less dangerous.

“Maybe there are some weapons out there that nobody should be able to buy,” Hayden said. “And maybe there are some people out there who shouldn’t be allowed to buy any weapons.”

Hayden is not too worried about large-scale, planned attacks involving multiple operators.

“The odds of that massive, mass-casualty 9/11 plot happening again are very, very low because we have really upped our game,” said Hayden, who also was the first principal deputy director of national intelligence. “So you end up with Orlando and Chattanooga and San Bernardino, which are very, very difficult to detect.”

In each Florida case, the FBI had looked into the attackers before they struck.

• In 2014, the agency investigated Omar Mateen, 29, of Fort Pierce, Fla., who killed 49 people June 12 at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Mateen had been linked to Moner Mohammad Abu-Salha, who had lived in Fort Pierce and Vero Beach, Fla., before blowing himself up outside a restaurant in Jabal Al-Arba'een in northern Syria.

• In November, Esteban Santiago, 26, of Anchorage, Alaska, who killed five last week at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, told the FBI that the CIA was controlling his mind and urged him to fight for the Islamic State.

Hayden warned of criticizing the FBI.

“When the Orlando guy was investigated by the FBI, he may not have been the Orlando guy who actually did the attack,” Hayden said. “There was a move there in his personality. It may be that the bureau didn’t miss anything … and he evolved into what he became.”

The question of safety is partly about freedom, said Hayden, who now works in the private sector at the Washington-based Chertoff Group security consultants.

“This all looks easy in the rearview mirror,” he said. “(But) how many false positives are you willing to live with? How many people who are never going to do us any harm are you willing to keep in jail or under surveillance?”

Then comes that question of trust. It’s clear from the 2016 election many Americans don’t trust their government, he said.

It’s one of the reasons Hayden, a former general who was the highest ranking military intelligence officer in the country before his Air Force retirement, wrote his recent book, Playing to the Edge: American Intelligence in the Age of Terror. In it, he seeks to demystify the world of spies, intelligence analysts and the like.

“Unless we get (the public’s) sanction or that legitimacy, I do fear for the future of American espionage,” he said, noting that the U.S. intelligence community, which employs about 100,000 people spending $50 billion a year, must be trustworthy.

“Obviously, we can’t tell all Americans everything we do. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be worth doing. Espionage is best done in secrecy," he said. "But we’re going to have to be more transparent about what we do.”

Part of his mission is telling the public that the espionage community is made up of people like the rest of us.

“They are almost viewed to be alien beings. … They are not,” he said of his peers. “They went to the same high schools you went to; they went to the same universities; they still go to the same churches.

“They’re just like your friends and neighbors, so don’t think for a moment people don’t share your values," Hayden said. "They are just asked to apply your values in circumstances you will likely never face and about which you will never know.”

Follow Laurence Reisman on Twitter: @LaurenceReisman