In unanimous decision, Supreme Court makes it easier for students with disabilities to sue schools

At issue: A student was receiving only about 4 hours of instruction a day, less than her nondisabled peers, because of a lack of accommodation for her disability.

WASHINGTON − A unanimous Supreme Court on June 12 made it easier for families to use the Americans with Disabilities Act to sue schools for damages, ruling a lower court used too tough a standard to dismiss a lawsuit from a student with a rare form of epilepsy.

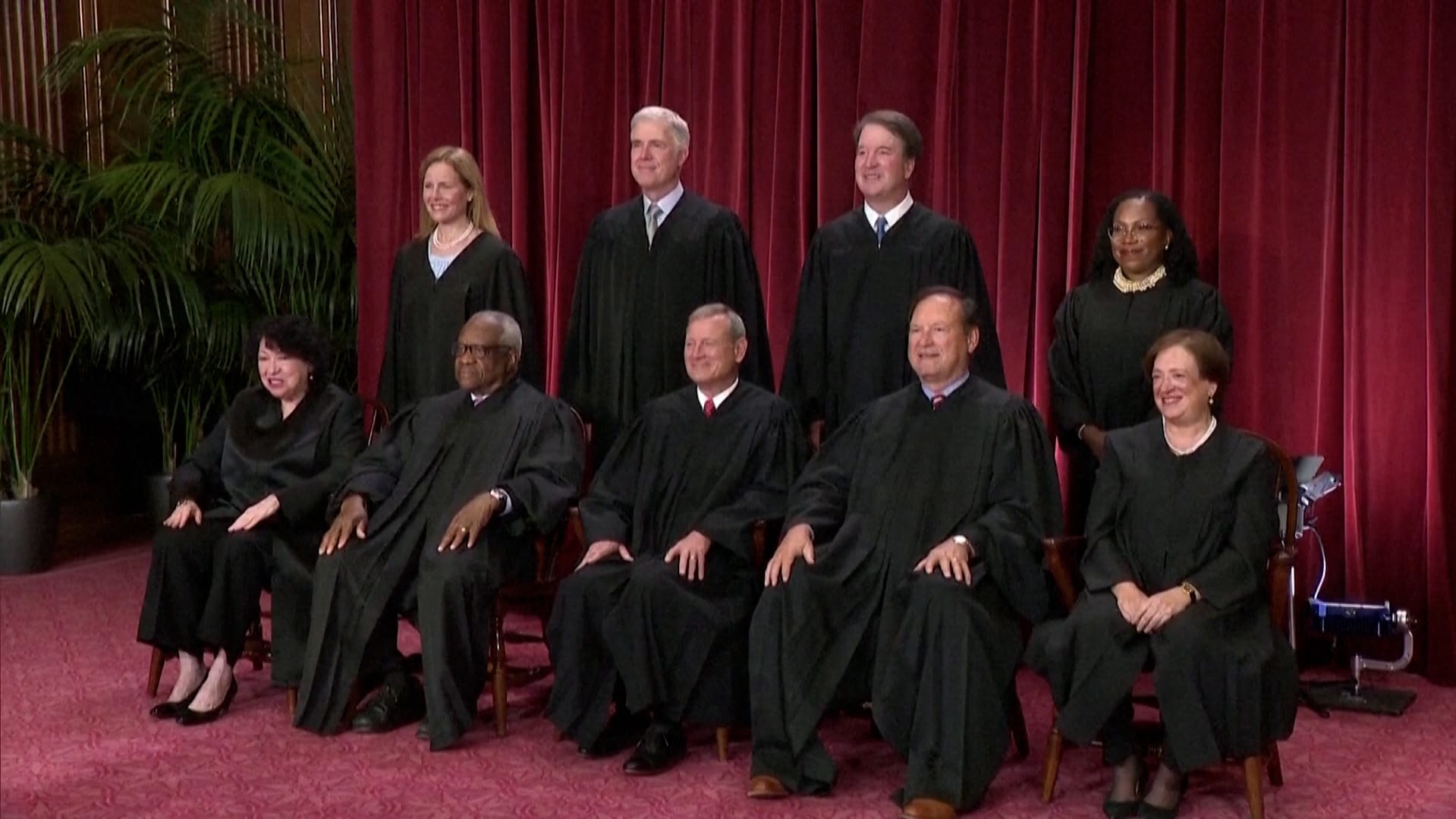

Writing for the court, Chief Justice John Roberts said the student’s family did not have to show the school acted in “bad faith or gross misjudgment." That’s more difficult to prove than the “deliberate indifference” standard courts often use when weighing other types of disability discrimination claims.

The court also rejected an argument from the school that would have raised the bar for all victims of disability discrimination rather than lowered it for educational instruction claims.

The case, A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools, was closely watched by disability rights groups. They say the courts have created a “nearly insurmountable barrier” for schoolchildren and their families.

But schools across the country worry that making lawsuits easier to win will create a more adversarial relationship between parents and schools in the difficult negotiations needed to balance a student’s needs with a school’s limited resources.

Seizures prevent attending school before noon

In this case, Gina and Aaron Tharpe said they spent years asking Osseo Area School District to accommodate their daughter's severe cognitive impairment and rare form of epilepsy called Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome. Her seizures are so frequent in the morning that she can’t attend school before noon.

A previous school in Tennessee shifted Ava's school day so it started in the afternoon and ended with evening instruction at home.

But the Tharpes say the Minnesota school system, where she is currently enrolled, refused to provide the same adjustment. As a result, she received only 4.25 hours of instruction a day, about two-thirds of what nondisabled students received.

Judge says school didn't do enough

When the Tharpes sued under the ADA and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, lower courts dismissed the case.

Judges on the St. Louis-based 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said their hands were tied because of a 1982 circuit decision – Monahan v. Nebraska − that said school officials need to have acted with “bad faith or gross misjudgment” for suits to go forward involving educational services for children with disabilities.

The Tharpes “may have established a genuine dispute about whether the district was negligent or even deliberately indifferent, but under Monahan, that’s just not enough,” the appeals court said.

School said there was no intentional discrimination

Hundreds of district court decisions across the country have been litigated under that standard, with most of them ending in a loss for the families, according to the Tharpes’ attorneys.

The Justice Department backed the Tharpes' argument that there should not be a different standard for disability discrimination cases involving education.

The school district’s attorneys pushed the court to apply a tougher standard for all cases rather than lower the bar for cases like Ava’s.

But because the school district didn’t make that argument until after the court agreed to take the case, the justices said they could not consider it.

“We will not entertain the District’s invitation to inject into this case significant issues that have not been fully presented,” Roberts wrote for the court.

Two justices said the school district raised an important issue that the court should consider in a future case.

“Whether federal courts are applying the correct legal standard is an issue of national importance, and the District has raised serious arguments that the prevailing standards are incorrect,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in a concurring opinion that was joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh. “That these issues are consequential is all the more reason to wait for a case in which they are squarely before us and we have the benefit of adversarial briefing.”

Ava's lawyers had warned that the school’s argument threatened “to eviscerate protections for every American who endures disability discrimination – and quite possibly other kinds of discrimination too.”

Roman Martinez, who represented the Tharpes, said the court's decision "gets the law exactly right, and it will help protect the reasonable accommodations needed to ensure equal opportunity for all."

“We are thrilled for Ava and her family," Martinez said in a statement.

The court's action revives, but does not settle, the Tharpes' lawsuit.

Attorneys for the district said the school had not shown “deliberate indifference," the lower standard.

Although the school declined to provide after-school support at Ava’s home, officials said they offered other measures to accommodate her needs while “effectively utilizing scarce resources shared among all students, including others with disabilities.”