The next pandemic apocalypse can be avoided, and other things I learned talking with WHO

They said we can be ready for it, and I remembered to take a breath.

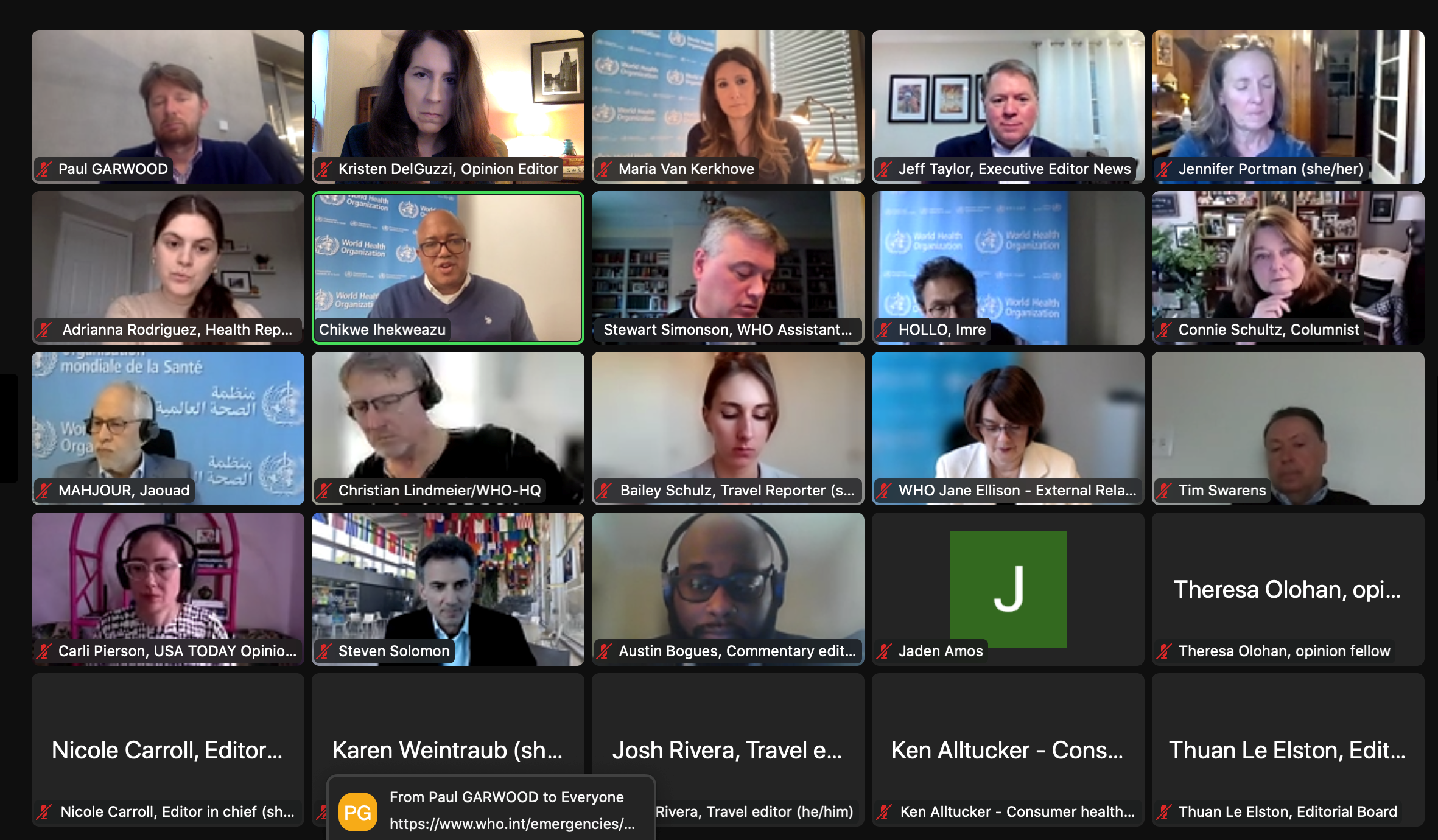

A recent conversation about the ongoing pandemic between Paste BN's Editorial Board and World Health Organization members included the idea that, for experts, it's more of a question of "when" rather than "if" there will be another pandemic.

My immediate thought: I would rather catapult myself into the atom-crushing gravity of a black hole than live through a similar experience.

But then they said that we can be ready for it, and I remembered to take a breath.

Pandemic apocalypse and space jokes aside – when President Donald Trump announced that he was withdrawing the United States from the WHO during the pandemic (and before we even had a vaccine), I was unsurprisingly horrified. If he had, for one day, taken his oath of office seriously then he would have known that the U.S. does not, and never did, exist in a vacuum. He would have also known that public health institutions provide a critical voice of common sense, and consensus, on global public health concerns. For instance, during a pandemic.

Opinions in your inbox: Get a digest of our takes on current events every day

It was through a global initiative that we eradicated smallpox in 1980 and, until recently, had nearly eradicated polio. The Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS is aiming for no new infections by 2030. These are massive achievements in medical history. Continuing to build and support these public health institutions, as WHO Assistant Director-General Stewart Simonson explained, "is the only way the next pandemic will be detected, mitigated and defeated."

Luckily for planet Earth and everyone on it, Trump did not win the 2020 election, and he can probably never hold federal office again if the House Jan. 6 committee finds Trump and company facilitated or participated in an act of treason.

Equally important: President Joe Biden wasted no time rejoining the WHO, the U.N. Human Rights Council and the Paris climate accord. For the time being, complete annihilation of the human species has been averted.

More from Carli Pierson: 'Don't Look Up' in pursuit of digital perfection. You might miss the end of the world.

The science didn't change. The policy changed.

And there is another lesson to be learned. From the beginning, doctors and public health experts had different concerns than people like me who barely got through high school biology. I know this because my partner is a surgeon, and from the time the pandemic started he was explaining to me how infectious respiratory diseases, masks and vaccines worked.

But, understandably, that's not what a worried, frightened American public understood. And, aside from the many examples of attempts to spread disinformation by the former president and others, it was in this way that the real experts' well-intentioned attempts to explain how families could protect themselves became convoluted, and people became increasingly more frustrated.

Overwhelmed by the requests for detailed epidemiological information in a way never before seen, public officials ended up splitting hairs and gave an overabundance of complicated data to a population not ready to receive it, or prepared to successfully use it. Some governments behaved considerably worse than others. Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, an American infectious disease epidemiologist and the WHO's COVID-19 technical lead, called the phenomenon an "infodemic."

But even without having to combat against deliberate campaigns of disinformation, making factually correct but complicated information simple enough for a global audience to comprehend and implement is very hard to do. From Day One, public health experts faced the Sisyphean task of explaining virology to nonexperts and communities as new variants continued to emerge. This, at a time when public trust in government in the United States continues to be at a record low.

More global opinion analysis: And meanwhile there's Iran – the other crisis that threatens the existing world order

Former U.S. Surgeon General: I got it wrong on masks at the start of the pandemic. This is how we can get it right.

In our conversation with the WHO, Dr. Van Kerkhove explained the lessons learned about the importance of untangling policy from science, as well as combatting politicized disinformation. Pointing out quarantines in different countries, she explained that people were blaming the science and confusing policy with data: "The science didn't change, the data didn't change, but the policy decision was modified to take into account risks and benefits."

She added, "There's no real point in in putting out massive amounts of information if we don't actually tell people how they can help themselves, to enable them."

I hear you, Doctor. I hope current and future world leaders are listening, too.

Carli Pierson is an attorney, former professor of human rights, writer and member of Paste BN's Editorial Board. You can follow her on Twitter: @CarliPiersonEsq