Black women made MLK's March on Washington happen. Yet their voices went unheard.

Black women have always been a crucial part of the civil rights struggle – not only as part of the masses and the marchers, but as masterminds of the movement.

The march came together blindingly fast. From conception to execution was less than three months. Finally, the day arrived, Aug. 28, 1963 – the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

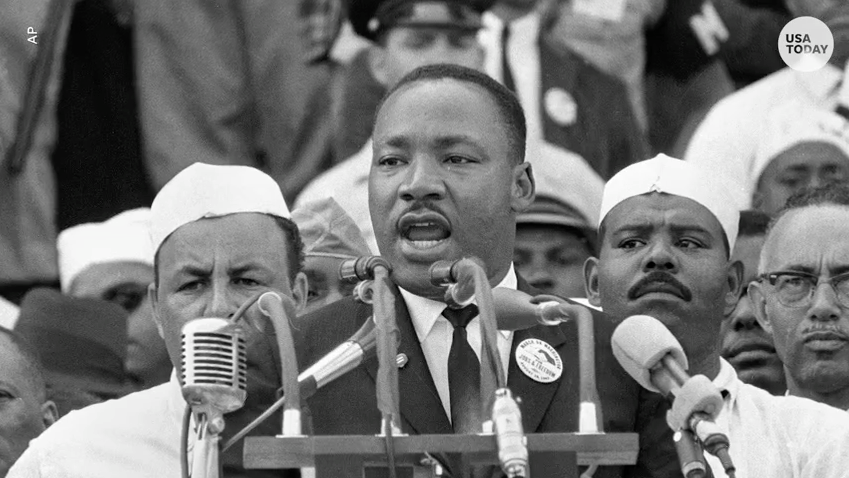

About 250,000 people came from across the country on cars, trains and buses to gather in support of Black civil rights and economic empowerment for the poor. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech to punctuate an already powerful landmark in the movement for equal rights.

Afterward, several of the key leaders met with President John F. Kennedy to discuss laws and policies that the marchers demanded. It was a resounding success on nearly every account – except for one conspicuous problem.

No Black woman served as a main speaker during the commencement.

Despite efforts behind the scenes, Black women weren't given the same visibility as Black men

Some women were featured in various other roles – activist and actress Ruby Dee emceed the event with her husband, Ossie Davis. Joan Baez performed. Mahalia Jackson sang the national anthem.

But no Black woman had a speaking role comparable with the Black men that day. Their relative invisibility at the microphone belied their integral involvement in planning and making the march happen.

Women such as Anna Arnold Hedgeman worked with the Commission on Religion and Race for the National Council of Churches, and she was the only woman on the powerful administrative committee planning the march. Her leadership proved vital in securing the participation of white Protestant Christians. She helped build bridges of cooperation between groups of white Christians and Black leaders who were understandably skeptical that white people would genuinely support this Black-led event.

Dr. King's message is fading: I helped write MLK's 'I Have a Dream' speech. Its message remains essential 60 years later.

In the aura of all the achievements the march represented, a group of Black women held a meeting called “After the March, What?” Dorothy Height, already a legend of the Civil Rights Movement and head of the National Council of Negro Women, convened the meeting. She had taken her place as one of the few key women organizers of the march and the only person representing an all-women’s organization.

Male organizers stood obstinately opposed to calls for greater visible participation of women. They made excuses like not wanting to arouse jealousy in women who were not picked to speak. Never mind the fact that men often displayed no lack of ego or pettiness in maneuvering for the biggest roles in the movement.

At the final planning meeting, Hedgeman stood up and read a letter that said, “In light of the role of the Negro women in the struggle for freedom and especially in light of the extra burden they have carried because of the castration of our Negro man in this culture, it is incredible that no woman should appear as a speaker at the historic March on Washington Meeting at the Lincoln Memorial.”

Her efforts resulted in only a symbolic concession. The male organizers agreed to have Myrlie Evers – whose husband, Medgar Evers, had been shot and killed in front of their Jackson, Mississippi, home for his role in leading the NAACP there – to give a “tribute” to Black women.

But she got caught in traffic and missed her part. Instead Daisy Bates, of the Little Rock Nine and the Arkansas NAACP, offered the tribute and said, “We will kneel in, we will sit in, until we can eat in any counter in the United States. We will walk until we are free, until we can walk to any school and take our children to any school in the United States.”

Black women are crucial to America's civil rights struggles

The “After the March, What” meeting the next day helped cement the resolve of Black women in the Civil Rights Movement to always elevate the concerns of women and families no matter what Black male leaders said or did.

Even other women’s groups led by white women were not much help. Black women did not feel that such organizations gave sufficient attention to the presence of racism, and they underestimated the role of poverty in issues of injustice.

Black women are fired up about Harris. We won't back down.

The meeting participants agreed that they needed to engage in more coordinated efforts that focused specifically on Black women.

In her memoir, Height later wrote about Black men’s views toward Black women in the Civil Rights Movement: “(Black men) were happy to include women in the human family, but there was no question as to who headed the household!”

That meeting of Black women led to another one in November 1963. There, Pauli Murray, a civil rights activist and lawyer, spoke about the need to attend to both racism and sexism.

“The Negro woman can no longer postpone or subordinate the fight against discrimination because of sex to the civil rights struggle but must carry on both fights simultaneously,” Murray said.

Black women have always been a crucial part of the civil rights struggle – not only as part of the masses and the marchers, but as masterminds of the movement. But Black women faced the dual oppressions of racism and sexism, often at the hands of Black men.

While their presence in front of the March on Washington was minimal, there can be no accurate assessment of that day and no adequate progress in civil rights without accounting for and honoring Black women of the movement.

Jemar Tisby is a professor of history at Simmons College of Kentucky. This piece has been adapted from his latest book, "The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance" and originally appeared in the Louisville Courier Journal.