Texas flood tragedy shows why local weather forecast offices are critical 24/7 | Opinion

Meteorologists perform another public safety service that takes place mostly out of view: constant communication with local officials in weather emergencies. What happened in Texas?

The Texas flood disaster, where the death toll has already well exceeded 100, has understandably sparked scrutiny of every aspect of the response, including the role of weather forecasters. President Donald Trump is expected to visit the scene this Friday, July 11. But a key takeaway is already clear. To keep people safe, it’s vital to recognize ‒ and support ‒ one critical resource: the nation’s network of local weather forecast centers.

The National Weather Service (NWS) may be a federal agency, but when it comes to public safety, much of the important work takes place at a local level. There are 122 weather forecast offices where meteorologists are on duty 24/7 to develop forecasts and issue warnings. In Kerr County, Texas, the epicenter of the flood catastrophe, that responsibility falls to the Austin/San Antonio office. (You can find where your own forecasts come from at this map.)

Now more than ever, it’s crucial for the public to understand the significance of these local offices, which have been battered by the Trump administration's staffing and budget cuts.

Job of meteorologists doesn't end with weather warnings

As a journalist who has spent the past five years researching and writing about the future of weather forecasting, I have an unusual perspective on weather forecast offices based on observing their work firsthand.

And that work is far more extensive than most people realize. Yes, meteorologists pore over computer models and radar displays ‒ applying their knowledge of local quirks of geography and climate to produce the most accurate forecasts possible. But the nation’s local forecasters perform another function that takes place mostly out of public view: constant communication with a broad array of local officials, broadcast media and other organizations upon whom we depend during weather emergencies.

Which is why every American should be concerned about cutbacks that impact weather forecast offices. The most difficult challenge is the last-mile problem. How well do forecasts and warnings get conveyed, and how effectively do people put them to use?

I saw this in 2022 when I observed meteorologists at the forecast office in State College, Pennsylvania. Forecasters met with public safety officials from Pennsylvania State University to discuss lightning threats at football games, when more than 100,000 fans pack into Beaver Stadium.

The forecasters also reviewed the school’s response capabilities, which include an emergency operations center working around the clock and an alert system for students. Both are among requirements to be certified by the National Weather Service as StormReady through an innovative program designed to foster local preparedness.

Other work included efforts to help the technology-averse Amish community keep tabs on weather and sharing heat wave safety tips on social media. All in a day’s work for one of these 122 local offices.

The story was similar when I visited wildfire country in San Diego. I learned about the consistent interactions among forecasters and relevant organizations whenever forecasts suggest risky weather.

Those conversations span meteorologists at the San Diego office as well as leaders at the region’s electric utility, first-response coordinators at Cal Fire, and local agencies that provide services during evacuations or power shutoffs.

The upshot is that keeping people safe from deadly weather requires that everyone talk with each other ‒ and that they listen to what forecasters are telling them. The NWS has worked hard for more than a decade to move well beyond issuing forecasts and increase the collaboration on public safety.

We need more than weather warnings to prevent loss of life

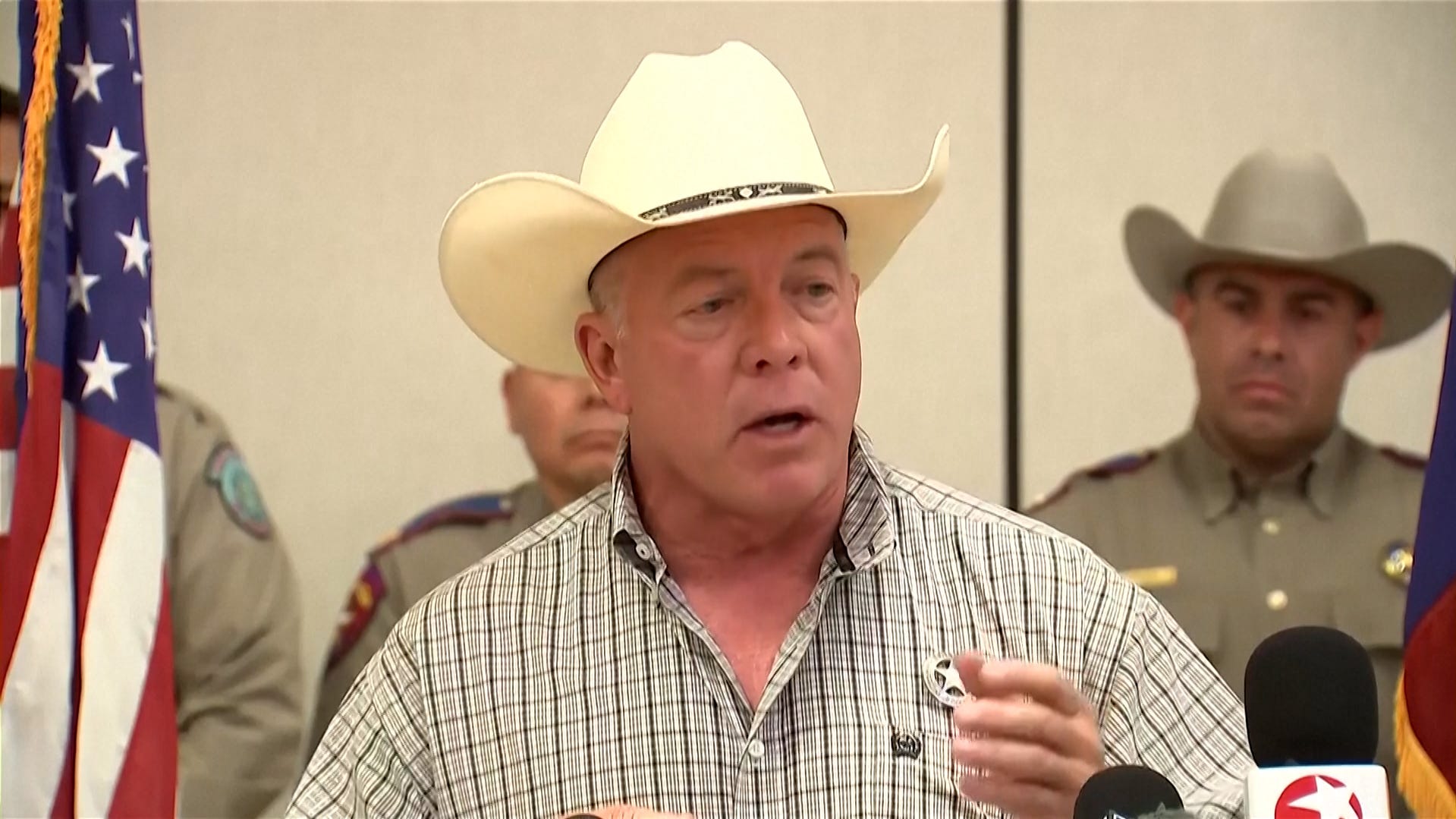

It’s too early to draw conclusions about what happened in Texas a week ago. Though some local and state officials have sought to blame forecasts, many weather experts who have examined the alerts from the Austin/San Antonio office have described the predictions as good.

Forecasters highlighted the possibility of heavy rains as early as June 29, then declared a flood watch on the afternoon of July 3 and issued a flash flood warning at 1:14 a.m. on July 4.

One focus will be how officials did ‒ or did not ‒ put this weather intelligence to use. For instance, there seems to be a four-hour gap between the flash flood warning and a message to the public from Kerr County officials on social media. Another will be the lack of a warning siren system, which some officials had previously sought.

The reality is that defending communities from extreme weather requires not only great forecasts but also planning and investment by local and state officials to put the information to work. That’s not always easy, particularly for non-meteorologists.

One cutting-edge approach was launched by New York in 2023. It’s called the State Weather Risk Communication Center. There, weather experts take forecasts and translate them into bottom-line decision guides for emergency managers, highway agencies, school districts and other officials across the state.

But none of this works without the forecasts, warnings and expertise of the local offices. I don’t want to suggest that predictions can’t improve; they can, and they will ‒ if the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service receive support. Yet the Trump administration plans more cuts, including to research necessary for better future forecasts.

We need America’s local weather experts on the job 24/7 ‒ and we need to keep getting better at using their warnings to prevent loss of life in tragedies like the Texas floods.

Thomas E. Weber, author of "Cloud Warriors: Deadly Storms, Climate Chaos ‒ and the Pioneers Creating a Revolution in Weather Forecasting," is a past executive editor of Time magazine and a former technology columnist for The Wall Street Journal.