Hubble Q&A with science rock star Neil deGrasse Tyson

Just as Hubble is a superstar among telescopes, Neil deGrasse Tyson is a superstar among astrophysicists. He has all the old-school, ivory-tower credentials anyone could ask for: a Ph.D. in astrophysics from Columbia, a posting as director of the Hayden Planetarium at New York's American Museum of Natural History, authorship of several papers using Hubble data to explore the evolution of the universe. But he also boasts more than 3.4 million Twitter followers and the label, bestowed by People, of "sexiest astrophysicist alive."

In the mid-1970s, a teenage Tyson spent a day at Cornell University with Carl Sagan, later host of the iconic TV series Cosmos. It was almost as if a baton had been passed. A few decades later, Tyson himself hosted a new version of Cosmos that was seen around the world. He spoke with Paste BN about Hubble, space travel and his new gig as host of what is in all likelihood the first science-based late-night talk show. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Q: What's your favorite Hubble image?

A: I have to say the Hubble Deep Field. Because every smudge, every blotch, every light blip on that image is an entire galaxy, with possibly a hundred billion stars within it. And then you stare at this and realize that, at arm's reach, it's a postage-stamp-sized patch of the night sky. And then you realize, "Well, if all of this is in this dull and boring part of the night sky, imagine what's elsewhere."

Q: Give us the back story behind that picture. It was the brainchild of the man running Hubble's science program, right?

A: The director of the Space Telescope Science Institute thought it might be interesting if he commandeered some time to take a picture of a completely empty, boring spot on the sky. The audacity of him, when you think about it! And out of that came one of the most famous images from the Hubble Telescope. It's a stunning profile of the contents of the universe.

Q: Which Hubble discovery should we all know about?

A: Most of the 20th century, people were arguing over how old the universe was. Our data were not good enough to decide whether the universe was 10 billion years old or 20 billion years old. One of (Hubble's) first tasks was to establish the age of the universe. And it did that. The age of the universe as discovered by Hubble is about 13.8 billion years. Now that we have the age of the universe, which we derive from the expansion of the universe, we can ask secondary and tertiary questions about the expansion of the universe. And only then do we discover that the universe is accelerating in its expansion.

I always like it when new questions arise simply because you are standing in a new place.

Q: Some experts say Hubble revolutionized astronomy. Others say it didn't. What's your take?

A: Is our understanding of the universe completely different with Hubble? No. Is our understanding of the universe completely better with Hubble? Yes.

I can tell you that the Hubble Telescope is responsible for more research papers and more collaborations with people from more countries than any other scientific instrument there ever was. In terms of sheer output and productivity, there's nothing like the Hubble telescope ever.

Now in all fairness, part of that is because the telescope was serviceable. And so it had a lifespan far longer than other telescopes that would be launched into space. Part of the productivity of Hubble has to do with how long the thing has been at it.

Q: Has Hubble had more success in its role as a scientific ambassador than in its role as a scientific instrument?

A: You know, it's hard to measure those. How do you compare two superlatives? Hubble came around at a time when people were just getting email accounts and just learning about a World Wide Web. And so Hubble with its digital imagery was perfectly timed and perfectly poised to bring the public into its home. (It) enabled them to embrace all that Hubble saw in the universe.

Q: Would you take a one-way trip to Mars?

A: No. (Laughs.) I think the premise is if you go one way, you're a little more resourceful and scrappy and you'll figure out how to survive. It's hard if you can't breathe. I would certainly go to tour the place, but I'd want to come back. I like Earth.

Q: What are the biggest obstacles to sending humans to Mars, besides money and political will?

A: It's money and will. You think there's a third thing? No. There are problems that have yet to be solved for space travel. But they're technological problems. It's not some law of physics that we have to somehow circumvent. I don't see engineering and technology as a barrier whatsoever.

Q: What do you think of NASA's plans to grab an asteroid and move it close to the moon for astronauts to examine?

A: I think anything we do in space that we've never done before is a good thing. We need some kind of practice touching and moving asteroids. Because one day we're gonna find one that's headed our way. And if we've never been to one and don't know how to move it — I don't want to be the laughingstock of the galaxy among aliens because we went extinct even though we had a space program and could have done something about it. (Laughs.)

Q: NASA hasn't sent humans beyond Earth orbit for a long time. If you want American astronauts to be in the space-exploration business, the trajectory isn't too good.

A: It's not. So let me dangle some carrots. It's pretty clear that the first trillionaire the world will ever see is the person to first mine asteroids and use the natural resources for space-based needs, as well as back here on Earth. And in fact, in a 60 Minutes piece there was a segment on rare earth metals and how most of them are mined in China. And rare earth metals are in every piece of computing hardware there is. And so why are they called rare earth elements? Because they're rare on Earth. But there are metallic asteroids where they are common.

So part of me wonders, "What are people thinking when they refuse to look to space for long-term solutions? What argument am I failing to make to alert people of this, 'cause it's really obvious to me?"

Q: What's the strangest thing about the universe?

A: For me, what's most fascinating about the universe is that it's knowable. That is fascinating. It could have been completely unknowable. Our intelligence level might have been below what is required to understand anything about it. But it's not. You know, we invent mathematics. And the universe speaks mathematics, right? We use math to decode the universe. That's kind of amazing. An invention of the human mind applies to the universe.

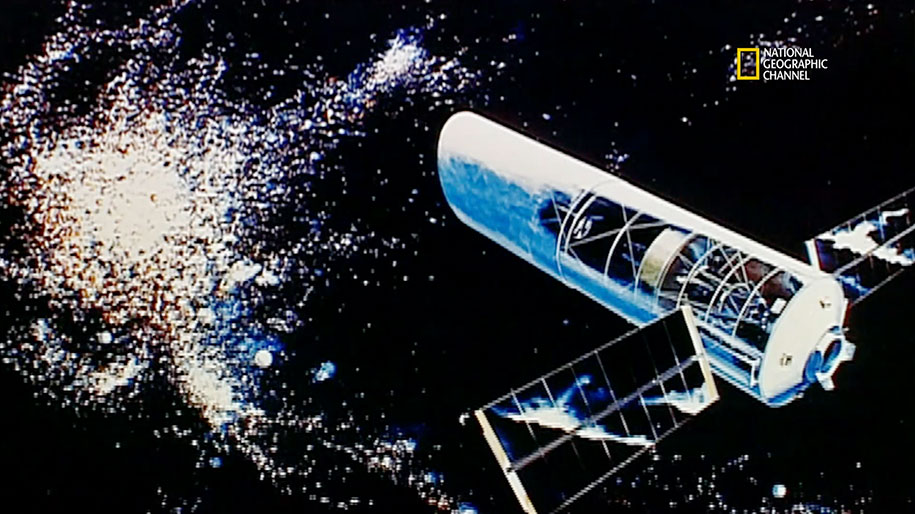

Q: You're hosting a new National Geographic Channel late-night talk show called StarTalk, which will be a TV version of your weekly radio show. (Premiere: April 20 at 11 p.m. ET/PT.) At the end of an episode, do you want people to walk away thinking, "Gee, I learned something new," or thinking, "Man, that was funny"?

A: Both. There are three threads that we stitch into a tapestry. One thread is science, another thread is pop culture, and a third thread is comedy. Late-night talk shows are very rich in pop culture, fun and silliness, right? I think there's never been a science talk show at 11 p.m. because nobody feels like learning anything at 11 p.m. You just want to relax. And so the challenge of Star Talk is — because I'm an educator and a scientist on top of all of this — can you be as entertained as you've grown accustomed to, but still end up learning something? That's what Star Talk is.

Q: Why switch from radio to TV? Isn't it a lot more trouble?

A: The Cullman Hall of the Universe (at the Hayden Planetarium), that's where we film the show. Otherwise, I do the show exactly as we did the radio show. There's no band. There's no monologue. There's no trappings of your typical evening talk show. But nonetheless — I looked hard, I couldn't find any examples — this may be the very first science talk show ever.

Q: You're going to have to dress up for TV, aren't you?

A: Yeah, I can't do it in my underwear anymore. (Laughs.) Yes, I'll be a little more groomed for television than I am for radio. Which reminds you that if someone says you have a face for radio, that's an insult, not a compliment.